Syllabus

The course takes a systems approach to examining the water resources of the U.S. West. Emphasis is placed on evaluating water resources from a variety of scales and perspectives, using the Colorado, Klamath and Columbia river basins as case studies.

Enrollment

This writing-centered course enrolls about 20 students from across disciplines, although they are expected to have background knowledge about human and earth systems. Several students have been inspired by the course to go into careers related to water resources.

Instructor

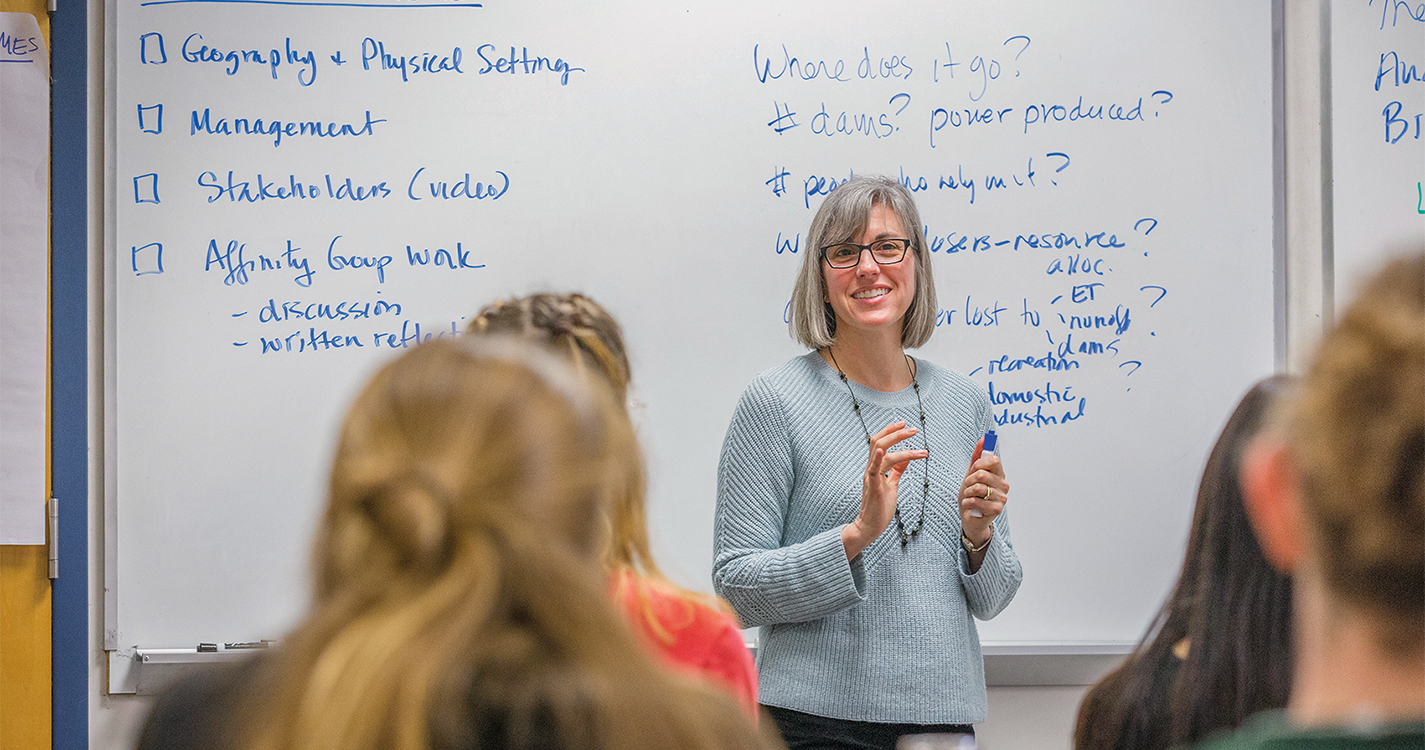

Karen Arabas, professor of environmental sciences, has been teaching this course since she arrived at Willamette almost 20 years ago. An East Coast native, she became fascinated as a graduate student at George Washington University by the complex story of Western water issues. Today, even her students from arid parts of the West, who are familiar with water conservation needs, are surprised to discover the complicated, interwoven natures of these crucial issues.

Highlights

Throughout the course, students work within a systems framework. This holistic approach views the Earth’s natural components, such as atmosphere, hydrosphere and biosphere, as interacting within one unified system. Human society is layered on top of — and affects — these natural systems and processes.

To clearly observe the interactions, students create elaborately charted and color-coded diagrams that show the flows of water between and within natural and human systems. They study each river in detail to see how the natural and human systems interact, and soon learn that each one has unique features — and problems.

The 257-mile Klamath River is an “upside-down basin” that starts in a flat agricultural area in south-central Oregon and travels through remote canyons to the ocean in California. As the river is a prime habitat for salmon, steelhead and rainbow trout, fishing rights for Native Americans are a key issue — and heated conflicts have arisen with local farmers who demand access to the water to irrigate their crops. In fact, about 80 percent of water in the West goes to agricultural use.

The 1,243-mile Columbia River, the largest river in the Pacific Northwest, originates in Canada and empties into the Pacific Ocean at the border between Washington and Oregon. With 14 hydroelectric dams on the main river, notes Arabas, “the Columbia has powered the development of the Pacific Northwest.” In particular, the cheap hydroelectricity supported the Hanford Site, a nuclear production complex established in southeastern Washington in 1943. Radioactive material was released into the river before site decommissioning began in the late 1980s, and future contamination of the Columbia by leftover waste remains a concern.

The final river studied, the 1,450-mile Colorado River, starts high in the Rockies and winds through 11 national parks, including the Grand Canyon, five U.S. states and two Mexican states before heading to the Gulf of California. Most years now, its water is used up hundreds of miles before it reaches the delta in Mexico, where a once-lush and thriving ecosystem is dry and desolate.

To meet the needs of about 30 million people in major metropolises including Denver, Salt Lake City and Los Angeles, the Colorado is diverted hundreds of miles via aqueducts. In a documentary watched by the class, one Los Angeles resident jokes, “Even the water commutes here.”

With such demand on its resources, the Colorado has earned the title of being the most litigated river in the U.S. — and probably the world. Arabas sees more difficulties ahead. Climate change is influencing precipitation patterns, which in turn affect the amount of water in the river basins.

“The Western U.S. was settled during a very wet climate period,” says Arabas. “It wasn’t designed to withstand the kinds of severe droughts we increasingly see. The problem is likely to get worse as the climate changes. It’s the looming issue for the future.”

A particular challenge

After learning about these problems with water resources, students wrestle with how to find solutions. “The texts we read often make broad, global suggestions, like ‘shift public perceptions,’ ‘instill respect for our environment and natural resources’ or ‘change public policy,’” says Arabas, “but they’re often not satisfactory because they lack details.”

So for the final exam, Arabas uses a simulation developed by Harvard Law School’s Program on Negotiation. Each student receives a packet of information about a water issue and a role as a stakeholder. They prepare a strategy briefing, role play during final exams and then write a follow-up essay. “It seems to do a nice job pulling the course themes together, and the students get very invested in the outcomes,” says Arabas. “Getting stakeholders to listen to one another holds out hope for solving these problems.”

This article was originally published in the spring 2018 issue of Willamette magazine.