Most of the time when a blue sky graces Salem in the middle of winter, I’m going to be pretty upset if I’m in class rather than riding my bike. Today was different though. We met to discuss logistics, itinerary, and most interesting to me-- Chinese economic trends in preparation for our study abroad trip from March 23 - 31.

In 1989, the year I was born, China’s GDP growth was 4.2% as estimated by the World Bank. That changed in the early 90’s. China’s GDP growth remained above 7% until 2015 (not to mention peaking above 14% twice, in 1992 and 2007). This is even more impressive considering China maintained its high growth rate during the 2008 financial crisis. To put things into perspective, global GDP growth never rose above 4.5% during the same period.

Couple China’s rapid growth with its world’s largest population of 1.4 billion people and we begin to understand the enormity of this shift and the effect it has and will have on global politics, economy, geography, and culture.

My mother was one of the first American students to visit China after relations with the U.S. were normalized in 1979. She remembers seeing thousands of bicycles and few cars in Guangzhou, the one city they were permitted to visit. I expect to see a country that, while possibly holding on to some traditions and values of the past, doesn’t resemble the China my mother saw as a college student.

As a student who will visit China in under three weeks, the questions I ask myself are:

- What tangible artifacts exist in China due to their industrial boom?

- How has life changed for the average Chinese citizen in the last 29 years?

- What’s it like to be a foreigner living and working in China?

I hope to see firsthand the answer to my first question, though my exposure will be admittedly limited in one week. We will visit Beijing and Shanghai, China’s two most populous cities. My understanding is that they are representative, if not emblematic, of the new, industrialized China. Considering that the western two thirds of the country are not as developed as the eastern coastline, I realize that I will only see one fragment of the prism. With that in mind, I’m excited to observe, take many photos, and perhaps converse if I find a willing English speaker or two. My Chinese language skills don’t exactly enable complicated dialogue.

The second question is one I could arguably answer through meaningful conversation with Chinese people, but perhaps I can begin to answer using available data. Using 1989 as a benchmark again, the urban population increased from 25.70% of the population to 57.96% by 2017. That’s over a 30% swing in rural-urban composition. Back in 1972, closer to the time when my mom visited China, just 17.18% of the population lived in cities. This is the difference between a traditional lifestyle on a farm and a modern, urban lifestyle in which one drinks Starbucks, shops on Alibaba.com, and rides public transit on crowded city streets. Or so I imagine. This data makes sense when coupled with the fact that Shenzhen grew from a fishing village of 5,000 to a global manufacturing hub of 10.7 million people from 1955 to 2015. There are no typos in the previous sentence.

The third question I expect to perhaps explore during my one week in China through conversations with expats I meet, though I will likely answer that better myself if I spend a semester in Shenzhen next fall, which I plan to do. I almost left this paragraph data-less as it’s more of a qualitative answer I’m looking for, but that wouldn’t be any fun. China’s Sixth National Census estimated that 71,493 American citizens lived in China in 2010, second only to Korean nationals.

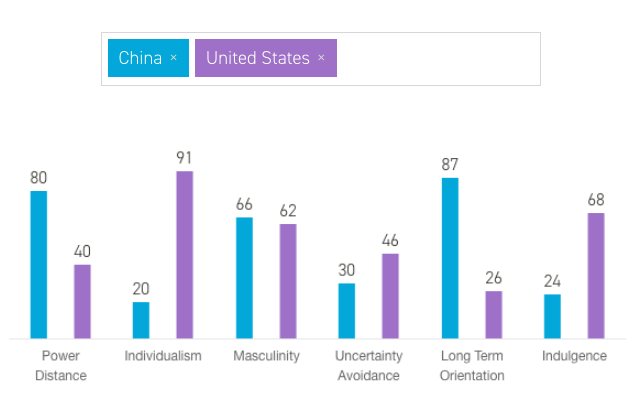

What might be more interesting to consider are the cultural differences between the U.S. and China. By Geert Hofstede’s six dimensions of national culture, the U.S. and China differ most in the following ways: power distance, individualism, long term orientation, and indulgence. The chart below compares each country’s score as assessed by Hofstede. For example, China has a much higher power distance in organizations than the U.S., meaning that Chinese organizations are generally more hierarchical than U.S. organizations. Additionally, the American culture is generally more individualistic than Chinese culture. China focuses more on long term instead of short term goals. Last, Americans tend to act more impulsively while Chinese are raised to be more restrained. The graph below provides scores for each country on those four dimensions.

I imagine that as a foreigner, these are the areas one could expect to feel the cultural differences most. When I lived in the Dominican Republic, I certainly felt the differences in individualism and power distance. No matter how adaptive we are, living and working in a foreign culture creates stress. Understanding where those stresses will come from helps us prepare for them and cope with them reasonably when they become a reality.

Speaking of China becoming a reality, we’re less than three weeks away from departure. I’m excited to send more updates as we get closer to departure and touch down in Beijing.