A patchwork blanket of red and navy plaid squares stretches 13-feet-high by 8-feet-long across the wall. Bright blue stitches form an outline of an animal’s underbelly and legs. An adjacent blanket highlights the creature’s head and neck in magnificent detail.

In this Portland art studio, a she-wolf has taken shape.

Over the last year, artist Marie Watt ’90 — the creator of the wolf blanket — has been thinking about the relationship between animals and humans. Watt is an enrolled member of the Seneca Nation of Indians. Her clan considers animals to be humans’ first teachers and relatives, partly because of their role in the Seneca and Iroquois creation story.

In this story, humans lived in the Sky World before the Earth existed. After Sky Woman fell through a hole in the sky, birds and animals rallied to assist her when she landed in what is now known as North America.

Watt sees the relationship between humans and animals as symbiotic. “If we don’t see our relationship (that way),” she says, “nature isn’t going to be there for us in the long run.”

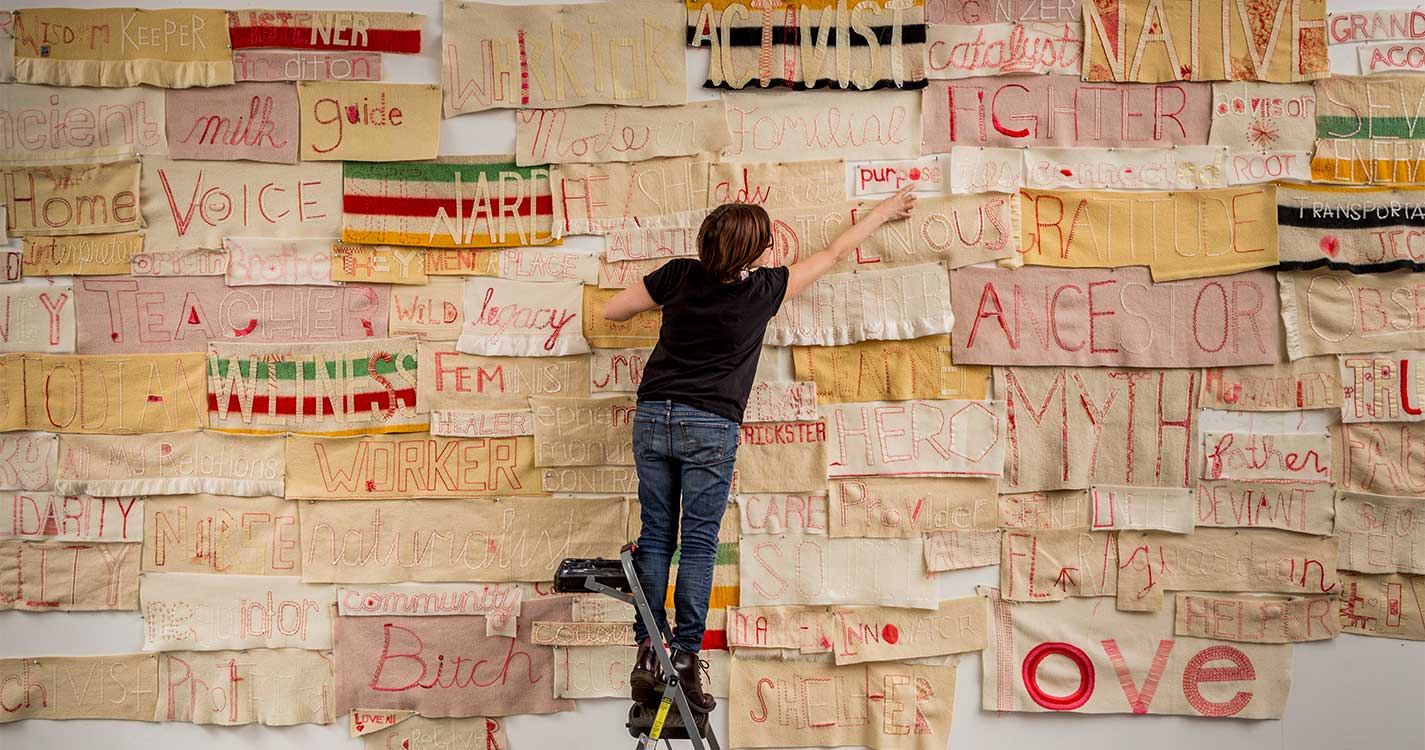

One of the country’s leading Native American contemporary artists, Watt is particularly recognized for her “Blanket Stories” installations — towering stacks of folded blankets, some as tall as buildings, all as varied in color and pattern as the stories behind them. One of these installations took place at and is now displayed on the Willamette University campus at the Hallie Ford Museum of Art, which owns several of Watt’s artworks and has held two major exhibitions of her work.

In her latest blanket project, Watt has reinterpreted the myth of the famous Capitoline Wolf and the founding of ancient Rome.

According to legend, the she-wolf nurtured Rome’s mythical twin founders, Romulus and Remus. Without her intervention, the city may have never existed. In Watt’s interpretation, the she-wolf represents nature as a provider of life for humans.

Watt incorporates indigenous beliefs, history and memory into her art in myriad ways. As she says on her website, blankets are everyday objects that “quietly record our histories: a lumpy shape, a worn binding, mended patches. Every (one) holds a story.” They represent varied meanings, too: shelter, ceremony within indigenous communities and life transitions such as birth and death, when blankets swaddle human bodies.

Last December, Watt installed the three-story “Blanket Stories: Textile Society, R.R. Stewart, Ancient One” at the U.S. embassy in Islamabad, Pakistan. The stacked 314 donated natural-fiber blankets signify the importance of cultural exchange in the Islamic world and its history of textile trade.

“Blankets feel global in nature,” she says. “They travel and move with us.”

After a whirlwind year of traveling for work, Watt — who in May 2016 received an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degree from Willamette University — still has more to do. In September, her she-wolf blanket — along with another one on a green material — will be featured at PDX Contemporary Art in Portland.

That same month, her work is featured again at Hallie Ford Museum of Art as part of a major exhibition celebrating the 25th anniversary of the Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts. On Sept. 23, Watt will also appear at the Willamette University College of Law in a panel discussion related to the exhibition.

Watt’s art projects are also known for celebrating the importance of personal and community memory — both in terms of the stories they tell and the way they’re created.

For her installation “Dwelling,” Watt asked community members to donate blankets and then invited donors — including a Nazi concentration camp survivor — to write their stories to accompany the project.

“Dwelling” appeared in the 2012 “Marie Watt: Lodge” exhibition at Hallie Ford Museum of Art, which also created a time-lapse video showing the installation of the work. To accompany the exhibit, the museum also published “Marie Watt: Lodge,” the definitive book on Watt’s art to date.

For the she-wolf installation, as with some of Watt's previous projects, members of a public sewing circle stitched the blankets.

As Watt says, “Every stitch is almost like a signature.”

Watch Watt talk about her work.