Quinlyn Manfull, a whip-smart Willamette University sophomore from Anchorage, Alaska, first started knocking on doors and calling potential voters for the Democratic Party as a 16-year-old high school student. In fact, she knocked on more doors for the November 2014 election than any other Democratic volunteer in the entire state.

But when Election Day came, the student with a passion for politics was too young to cast her ballot — something she describes as “heartbreaking.”

Now 18, the politics and economics double major is campaigning hard for her favorite presidential candidate: Hillary Clinton. Last spring, she called Alaskan voters from her dorm room in Salem, and during spring break, she volunteered at and voted in the Alaska Democratic Caucus. Come November, Manfull ’19 might be one of the most eager students on campus to vote in her first presidential election.

Her enthusiasm, however, is coupled with unease.

“I’m scared, to say the least,” Manfull says. “And I really wish I weren’t, because in another circumstance, I would be extremely excited because I think Hillary Clinton will be a phenomenal president. But I am scared because of the whole Donald Trump situation and a lot of the vitriol he has created and promoted.”

Manfull is not alone in feeling apprehensive. Ask students and political scholars across campus for their thoughts about the presidential election, and words like “anxious,” “disappointed,” “unprecedented” and “unusual” come up frequently — and they’re talking about both Trump and Clinton.

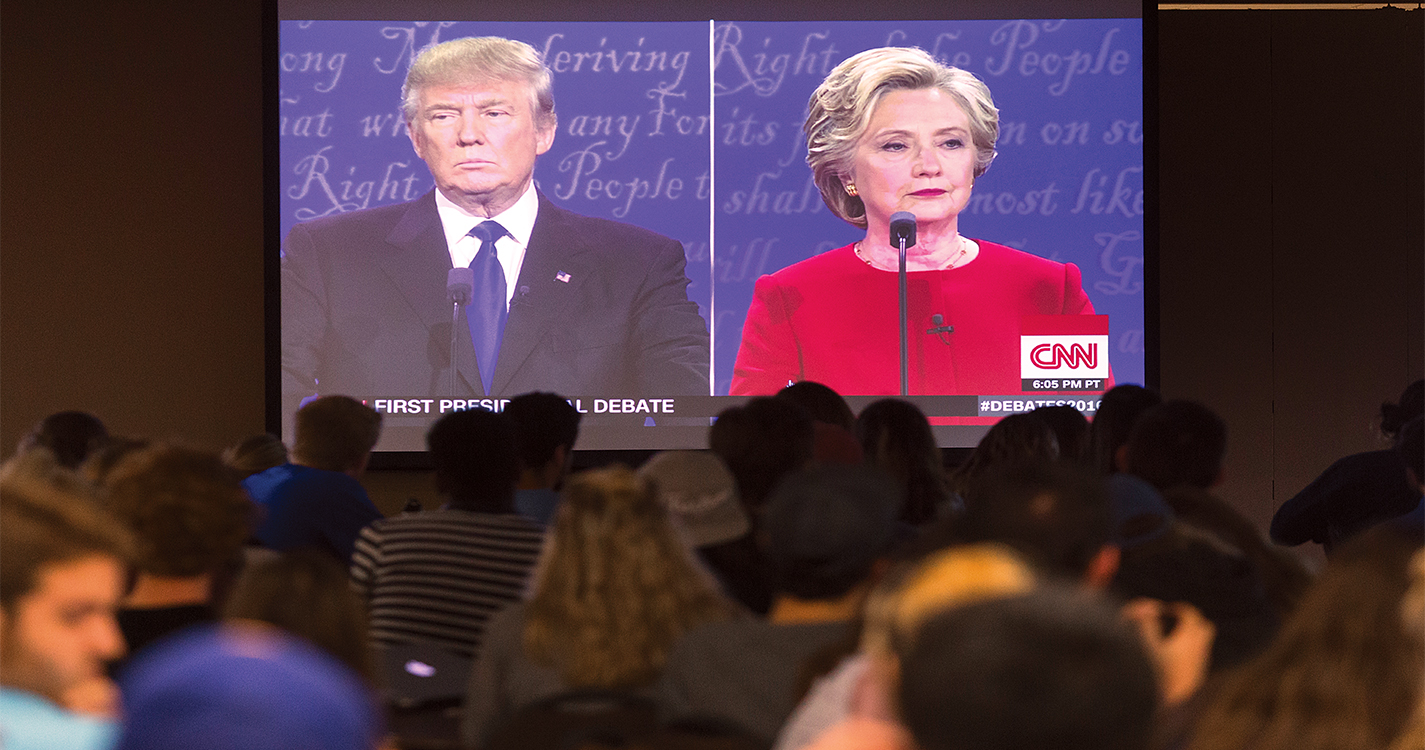

Nationwide, many voters are scratching their heads at how we came to this point with these two major candidates: a Republican outsider with no experience in office, whose controversial actions have led more than 100 leaders in his own party to say they won’t vote for him; and a Democratic insider who battled a potential indictment as well as a tough opponent whose die-hard supporters fought long and hard against her and the system she represents. A Gallup poll in mid-July showed that one in four Americans disliked both candidates.

“I think it is unfortunate that the first election I will be able to vote in is one in which I’m not necessarily going to be proud to cast a vote in either direction,” says Tyler Harris ’17, who is president of Willamette’s College Republicans but does not support either major candidate. “This is a massively disappointing circumstance and really a concerning thing for many people in our country and around the world.”

The unusual nature of this election led many professors of politics-related courses, even those who have taught about elections for years, to re-tool their syllabi and re-examine the ways they addressed the topic this fall. Their guidance in how to analyze candidates and the political process can be critical to college students preparing to vote for president for the first time.

“This election looks so different and raises so many new questions,” says associate professor of politics Melissa Michaux, who teaches “Parties, Elections and Campaigns” every four years. “I don’t think we’ve ever had an election quite like this one, where there’s a real possibility of a breakup or disintegration of the party system that we’ve had in place.”

What’s different this time?

Politics professor Richard Ellis, a nationally known expert on the American presidency, has written books on how the presidency was founded and how it developed into what it is today. He admits that it’s tempting, as a historian, to say this election isn’t that different from some in the past. Yet, he struggles to make that claim.

“If it had been Hillary Clinton versus Ted Cruz, it would have been a divisive and bitter election, but I don’t think that would have been anything new,” Ellis says. “Trump does feel new. You’d be hard-pressed to find another major party nominee in the past 50 years who has had so many people from their party’s intelligentsia, as well as former elected and government officials, who have distanced themselves from and won’t endorse their party’s nominee.”

Many of those Republican leaders based their denouncement of Trump primarily on his contentious rhetoric. So many, in fact, that at the end of August, The New York Times posted an online graphic titled, “At Least 110 Republican Leaders Won’t Vote for Donald Trump. Here’s When They Reached Their Breaking Point.” The graphic depicts two vertical timelines comparing “What Trump Said” to “When They Walked.”

Politics professor Michael Marks, who taught “Political Metaphors” last spring, attributes Trump’s use of provocative rhetoric to one reason: It works.

“Trump doesn’t speak in terms of broad metaphorical concepts like progress, and apart from ‘Make America Great Again,’ he rarely presents slogans,” Marks says. “He talks to people like they talk. They feel, in a weird sort of way, less talked down to because he doesn’t use slogans that they feel are devoid of meaning, like a lot of other politicians do.”

But it’s not only Trump who has changed the rhetorical dynamic of the campaign, says Robert Trapp, director of the Willamette Debate Union and chair of the Civic Communication and Media department.

“It’s the most divisive election that I have ever seen,” Trapp says. “I blame Donald Trump for a lot of that, but he’s not the only one doing it. There is so much name-calling on both sides. Some of the early Bernie-Hillary debates were good — they both got to express their arguments, and we learned a lot. As the election tightened, they just got mean.”

The tensions between Bernie Sanders supporters and Clinton supporters during the hard-fought Democratic primaries often led to vicious personal attacks. Manfull experienced this firsthand while trying to promote Clinton to other voters at the Democratic Caucus in Anchorage. Sanders followers greatly outnumbered those for Clinton (he ultimately won the state caucus with 81.6 percent of the vote), and they were aggressive, she says — calling her unprintable names when she asked them to stop filming her as she talked with voters.

“The primary was a scary time for me in terms of being a Hillary supporter because things like that were happening all the time,” she says. “You had to deal with attacks from the left and from the right, and sometimes they were the same attack.”

On the Republican side, despite Trump’s incendiary rhetoric and the best efforts of the “Never Trump” Republicans, the fundamental dynamics of the race have remained largely familiar, Ellis says — which is surprising in itself.

“If you look at the polls, the states in play are mostly the same as in 2012 and 2008,” Ellis says. “One sure sign of our hyper-polarized politics is that Trump has a floor below which he doesn’t seem to sink, no matter what he says or how many Republican elites distance themselves from him. However, the really important question is, ‘Where is his ceiling?’ and the answer to that question seems to be ‘not high enough to win.’”

Shifting classroom discussions

In mid-August, just two weeks before fall classes began, several Willamette professors teaching classes about the election said they still were finishing their syllabi — a tough task when the dynamics of the race kept changing, sometimes daily.

“What I was wondering all summer was how does the way we’re going to end up talking about the election shift because of the way the people involved do and don’t use evidence,” says associate professor of sociology Kelley Strawn, who is teaching “Public Opinion Polls and Surveys: Understanding and Evaluating Information in an Election Year,” a College Colloquium class for first-year students.

“We seem to be way out there into the realm of public people willingly making stuff up. And I don’t just mean Donald Trump. When Hillary Clinton says that the FBI director said her statements were truthful, I think, ‘No, he didn’t. He said he couldn’t prosecute you.’”

Strawn led his students through the methodologies of how polling works before tackling the various ways people use the results, from the common voter who is curious about how the candidates are doing to the politicians who rely on the data to plan campaign strategies.

“There is civic responsibility embedded in the questions we address,” Strawn says. “How do you make decisions? How are you going to be critical of the information you’re receiving? Which information will you trust, and which will you not trust, and why? What a great thing to work with, especially with 18- and 19-year-olds who will be voting in their first election.”

Strawn says people often discredit polls when they don’t accurately predict the election outcome. But the problem isn’t the polls themselves, he says — it’s that you’re asking voters to predict an action they will take in the future.

“Polls should be trusted only for what they actually tell you, which is the candidate people think they would vote for if the election were today,” he says. “It does not mean that they’re going to. Tomorrow, they could change their mind.

“Still, it’s appropriate that we’re all being skeptical of polls in the current election, because it’s not following patterns that historians, political scientists and sociologists have identified in recent elections that would predict who wins.”

In her “Parties, Elections and Campaigns” class, Michaux typically teaches students the purpose and role of the party system while examining how it developed over time. This year, she and her students are grappling with a new question: Are we at the end of the useful party system?

“It’s interesting that Trump did better in states with more open primaries, as did Bernie Sanders,” she says. “Historically, we really have needed political parties to overcome the institutional fragmentation and decentralization of our system. One of the questions I’m asking in my class is, ‘Are parties still serving that function, or does this most recent election finally challenge us to think about how to serve that function in other ways?’”

When Ellis taught “What’s the Matter with American Politics?” last spring, he and his students spent much of the time trying to identify the reasons for Trump’s rise. Ellis says that he works to assign a wide range of readings that showcase different perspectives and ways of approaching a subject. But during class discussions, the idea of “balance” is less important to him than “searching for the truth, as you see it, and respecting the truth as other people see it.”

“I think it’s important to create a space where everybody feels that their points of view, backed up by evidence, are respected,” he says.

“I don’t talk in the classroom about whether you should vote for Trump or not. But I don’t feel the need to pull punches when Trump or his supporters say or do things that are genuinely alarming or dangerous, especially when his rhetoric and that of his supporters closely parallel authoritarian, ethnocentric and xenophobic appeals in the American past and that of authoritarian leaders and movements across the world, past and present.

“The reality is that Trump’s success, whether he wins or loses the election, is a sign of how much is wrong with the current state of democracy in this country. It starts with an ill-informed and distrustful public, a polarized political elite, a media driven by the imperative to maximize clicks and views, and national political institutions that have become hopelessly gridlocked and seemingly incapable of constructively addressing the many real problems the country faces.”

Students weigh in

Gerardo Jauregui ’17 has complicated feelings about this election, but he sums them up with two words: anxiety and suspicion.

The fast-talking international politics junkie has a long list of why he’s feeling anxious. Because the next president will be appointing at least one new Supreme Court justice, who could impact such issues as immigration reform — an issue that is particularly important to him as the son of Mexican immigrants. Because Trump’s rhetoric around foreign policy is “problematic and alarming,” he says, especially in regards to issues like banning Muslims from entering the country and providing only conditional support to NATO members.

His suspicion is directed at both Trump and Clinton. Her actions relating to the Benghazi attack and the email scandals make him question how she might handle difficult issues as president. “Having trust and integrity will be really important for whichever candidate gets elected,” he says. “There is a lot of suspicion among many voters of both Clinton and Trump, and that will have long-ranging implications.”

Despite his reservations about Clinton, Jauregui says he plans to vote for her in November. That’s true for a historic number of younger voters. A USA Today/Rock the Vote poll conducted in mid-August showed Trump gaining just 20 percent of the vote among people younger than 35 — compared to 56 percent for Clinton — the worst showing for a major candidate among young voters in modern American history.

Multiple Willamette students — both Democrats and Republicans — cite Trump’s attitudes relating to racial, ethnic and religious tolerance as major factors in why they do not support him.

Harris, the College Republicans president, said in late August that the chapter would likely not endorse Trump (they had not decided by press time). He says, “We’ll have a conversation as a club about whether this is the point at which our moral standing conflicts with the current direction of the Republican Party.

“Personally, a large part of the reason I’m not a Trump supporter is because he hasn’t, as a candidate or as a businessman, engendered the kind of reputation that allows me to put my trust in him unconditionally. On top of that, there are all of the issues with his rhetoric that I share with a lot of my friends across the political spectrum. … His statements about a lot of ethnic and cultural groups have been distasteful at best and terrifying at worst.”

Jauregui, like many young voters on the Willamette campus, was a Sanders supporter during the primaries. Despite feeling that Clinton’s experience as secretary of state placed her in a better position to manage foreign policy, he was attracted to the “unparalleled level of discussion” that Sanders brought to issues like education, immigration, economic inequality and prison reform. And he appreciated the way Sanders energized many young voters.

Anna Carlin ’17, president of Willamette’s College Democrats, hopes she and other politically active people on campus can capitalize on that excitement to get students more involved in both the presidential race and the campaigns for other offices and ballot measures.

Carlin has been a Clinton supporter all along — she has three Clinton stickers on her water bottle and laptop, and wore a Clinton T-shirt to her interview for this story. But she recognizes that many other students are skeptical of her chosen candidate. “A lot of people on this campus are Bernie supporters, and it makes sense because his platform was a lot more youth-focused,” she says. “But Clinton is, in my mind, one of the most highly qualified presidential candidates we’ve ever had. There’s a lot to get excited about with her.”

Although she has clear views of whom she supports and why, Carlin still struggles with how to make sense of her first presidential election as a voter. “There are points where I feel like I’m going to wake up and it’s going to be last November, when the Republican debates were just getting underway, and none of this election will be real,” she says. “It just feels so surreal and at points absurdist.”

Many students look to their classes — like those taught by Strawn, Michaux and Ellis — to help them on the path to making an informed decision.

“My classes have helped me better understand foreign policy and economic policy, which are extremely large issues in today’s elections,” Manfull says. “Being a better learner, a better listener and a better consumer of information are things I have grown in while I’ve been at Willamette.”

Jauregui feels the same. He credits Marks, his politics advisor, with kindling his interest in international affairs while showing him how to analyze issues with a wider lens.

“When a candidate proposes things like conditions on NATO members, my initial reaction is to use what I learned in class about international relations theories, and I apply that to the candidate’s proposals,” he says. “At the end of the day, I have to decide if what I think is right aligns with what a candidate is proposing.”

Just vote, already

No matter what the tone of the election, or how different it might be from those of the past, Willamette professors say they still convey one message that endures.

“I make it a point never to tell people how they should vote, but that they should be informed and that they should vote,” Strawn says. “Make your own decision, and do it with good information, but go do it.”

Ellis typically concentrates on this point in his introductory American politics course, which includes many younger students who are not politics majors and may not be as interested in elections. He requires them to read the Washington Post online daily, in hopes of setting the stage for them to become well-informed voters.

Ellis also teaches students about how elections work and why they are important to the overall political process.

“The basic structural problem at the moment is that young people vote in presidential elections and then don’t vote in local, state and off-year congressional elections,” he says. “I’m trying to get the students to see why young people don’t vote and what difference that makes to the kinds of outcomes we get.”

For many of Willamette’s politically active students, the message is getting through — even if they struggle with the unusual nature of the election. Harris, when asked in August, had not yet decided who would receive his vote. But he knew one thing for sure: he definitely would submit his ballot.

“To not vote at all is a waste,” he says. “It’s a waste of the right to be a part of our democracy, and it is tantamount to saying you would rather hide and deal with the consequences of others’ decisions than to be actively involved yourself.”

Sarah Evans is a freelance writer in Salem.

Willamette, the magazine of Willamette University, is published by University Communications. Its purpose is to share stories and conversations that help alumni and friends stay meaningfully connected to the university. The views presented in Willamette do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the editors or the official policies and positions of Willamette University.