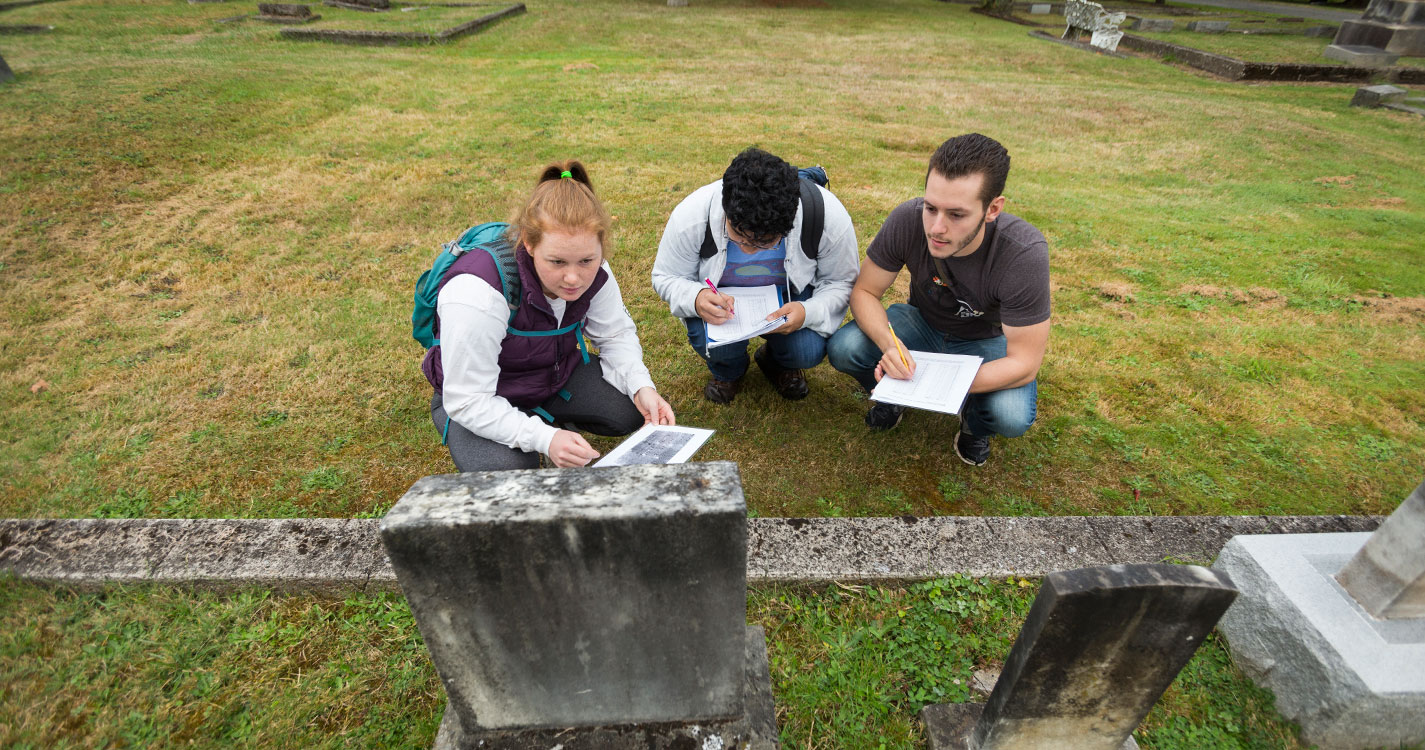

Clusters of Willamette students huddled around tombstones at one of Salem’s oldest cemeteries, carefully examining the inscriptions.

Scott Pike, associate professor of environmental earth sciences and archaeology, quizzed students on the types of stones they would encounter. Tombstones are commonly made of granite and marble.

“What’s marble made out of?” he asked. “Calcite. My favorite mineral, my favorite stone.”

The goal for last Wednesday’s science lab was simple: Identify at least 40 marble headstones at Pioneer Cemetery, jot down the inscription date and use a chart to estimate the rate at which the stones had weathered due to exposure. Afterward, the class would interpret the data using Excel to calculate the weathering rate and assess the quality of their information.

The lab was one hands-on activity for “Earth system science,” a required course for environmental science and archaeology majors that provides an overview of the Earth’s systems and its history.

Pike is well-known for leading student groups on excavation trips to the Orkney Islands in Scotland, but his students also explore research-rich locations closer to home. The previous week they visited Silver Falls State Park, where they learned about the geologic history and processes responsible for its famed waterfall. To develop their abilities to record geologic observations, students also sketched the South Falls and identified different basalt flows and sedimentary layers.

The lab aims to help students to become more observant, develop their quantitative analysis skills and gain practical experience using spreadsheets to evaluate data.

Elisabeth Calandra ’19 says the lab provided important information about how the Earth functions. But the science class also offered insights about the human condition.

“The assignment presented a juxtaposition of how people are remembered,” Calandra says. “Gravestones exist so people can be remembered, but the weathered gravestones counter that idea.”