It’s a few minutes past 8 a.m., and many of the sleepy students gathered in the Eaton Hall seminar room look as if they’d much rather crawl back into bed than debate the French Revolution.

“How are you all not interested?” Bill Duvall yells suddenly, pounding on the desk for emphasis. His blue eyes flash as he surveys the now-alert students. “Come on! There’s sex, prostitution, political corruption and violence!”

Over the past 45 years, students taking the legendary history professor’s classes have witnessed many such dramatic scenes intended to jolt them into an awakened intellectual state. Duvall has even been known to jump on top of a desk and wave his arms in the air to drive home a point about Foucault, Nietzsche, Sartre or some other European intellectual luminary.

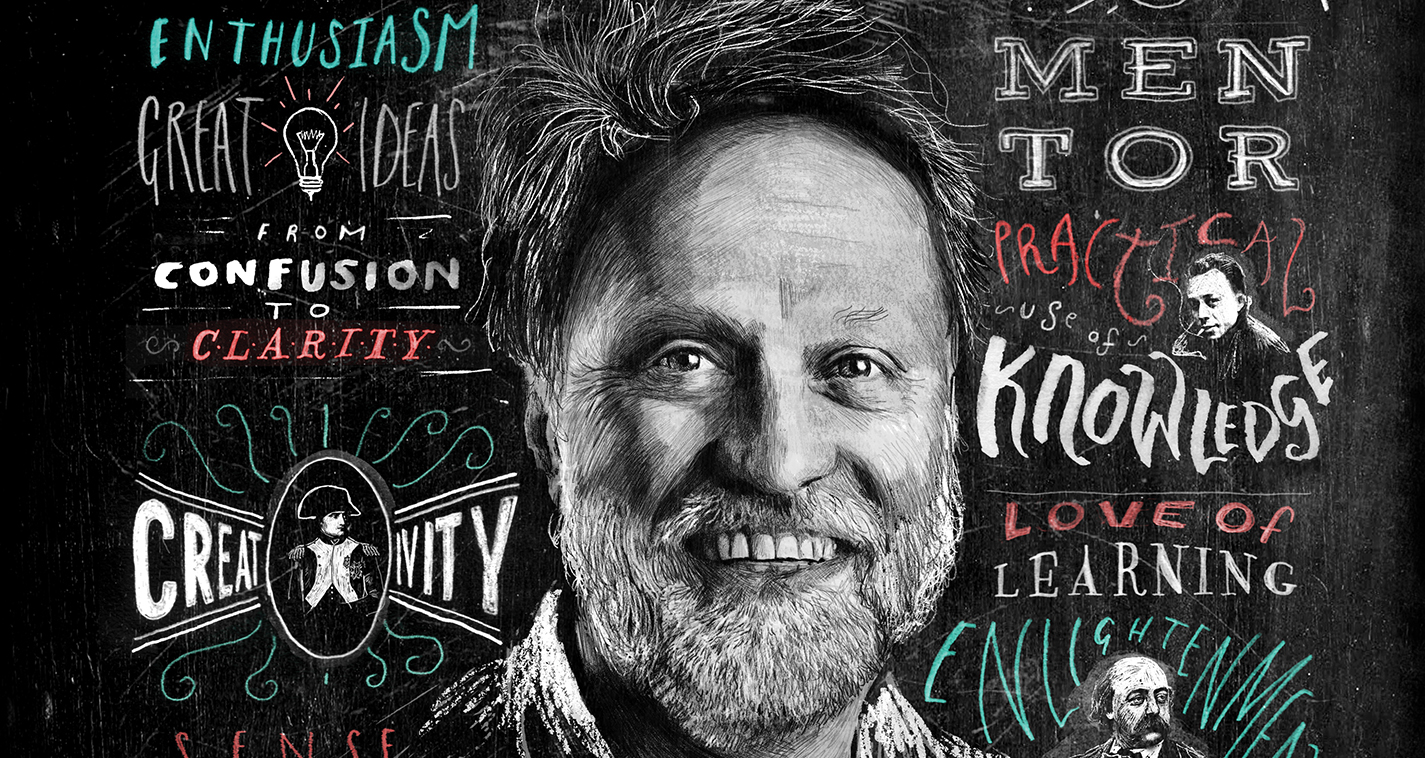

Such incidents only feed his reputation as a charismatic — and contradictory — character. Many students adore him; others chafe at his no-nonsense style. Some people describe him as a brilliant academic and a caring mentor; others call him an “intellectual provocateur” and “an anarchic lone wolf.” That last description probably delighted the man who likes to joke that he went into academia so he’d never have to work a day in his life.

In fact, Duvall did work one previous job: a half-day at a Wonder Bread factory before he was fired for not keeping up on the production line.

While an academic’s work may not be as physically onerous as a factory worker’s, the life of the mind requires hard effort and presents unique challenges. Duvall successfully met those challenges. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Whitworth College in Spokane, Washington; a master’s from the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia; and a PhD from the University of California, Santa Barbara.

At Willamette, he has not only taught intellectually rigorous history courses, but he achieved the rare feat of getting students excited about texts like Kant’s “Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics.” He excels at leading the small-group seminars that require professors to possess both the comprehensive knowledge to guide the discussion and a nimble mind to follow the conversation’s leaps into unexplored areas.

As director of a three-year National Endowment for the Humanities grant, Duvall helped design Willamette’s first freshman seminar program, World Views, and later the Faculty Colloquium series. Along the way, he amassed a collection of teaching honors, including the 1998 Oregon Professor of the Year Award.

Duvall’s favorite song is Tears for Fears’ “Badman’s Song,” and Willamette’s own radical has often delighted in swimming against the current. He served as draft counselor for students seeking conscientious objector status, and in the 1980s he pushed the university to divest its financial interests in apartheid South Africa.

In one of the few grainy photographs of him that exist, Duvall sports a checked shirt and a large, bushy beard. He looks more like a lumberjack than a scholar.

When he decided to retire at the end of the past spring semester, Duvall hated the idea of a “big fuss.” Eventually, he consented to a public lecture in his honor, given by his former Willamette colleague, history professor Myles Jackson. Despite his tough outer shell, Duvall was visibly touched by all the students, alumni, faculty and staff who packed the lecture hall and sent him commemorative letters of well-wishes, appreciation and fond memories.

A Willamette tradition

In his passion for his subject and his ability to inspire his students, Duvall represents the best kind of teacher. Yet he insists he’s nothing out-of-the-ordinary. Especially not at Willamette.

“The university has a long tradition of people who are great in the classroom,” he says, checking off the names of “academic giants” such as Ivan Lovell, Chester Luther, Howard Runkel and George McCowen. “It’s a thrill to have that sense of heritage, and I flatter myself to think that I’m in the same position that Ivan Lovell held, teaching the same courses he taught.”

Willamette’s history of teaching excellence isn’t “one-size-fits-all,” Duvall adds. Instead, it’s diverse, encompassing different styles and approaches. “Great professors don’t all do things the same way,” he says. “Team-teaching showed me things that I couldn’t do but that other professors do really well.”

While Willamette professors may be unique in their approaches and personalities, they share some common qualities. The stacks of nomination letters for the Oregon Professor of the Year Awards yield insights into the stellar teaching that takes place across campus. In addition to those accolades, Willamette faculty regularly receive other awards, whether from the Mortar Board student honor society, their university colleagues or external organizations.

“Students come to a small liberal arts institution like Willamette rather than universities with huge lecture halls because they want this kind of teaching,” says Duvall. “They want to find a place where they fit. People who teach at this institution and the students who come here — they’re kind of made for each other.”

Duvall knows from personal experience what happens when the institutional “fit” is wrong. In 1970, he accepted a job at California State Polytechnic University, San Luis Obispo, teaching general education history classes to the sons and daughters of San Joaquin Valley ranchers. “The kids wore crumpled cowboy hats pulled down over their eyes, had cigarette packets tucked in their sleeves, and practiced roping bushes between classes,” he recalls. “They weren’t interested in European intellectual history.”

The examined life

Willamette, on the other hand, attracts both students and faculty interested in developing what Socrates would call “the examined life.”

One former student of art history professor Roger Hull, the 1993 Oregon Professor of the Year, commented on Hull’s ability to inspire a “lifetime commitment to discovering the pleasure and profundity of human experience.” The student added, “Good teaching is about one’s life, not just one’s experience of the classroom.”

Faculty like Hull and Duvall have loftier goals than simply helping students pass a test or earn a degree. They want to introduce them to the life of the mind, an enduring intellectual fervor that leads to rewarding experiences, ideas and opportunities. One of Duvall’s former students said, “Bill’s great talent as a teacher is to make students love ideas, to learn to trust their own ideas and to value intellectual debate.”

Another student said what he learned in Duvall’s classroom changed both his personal evolution and the course of his life: “As the product of a middle-class family in a small Oregon community, I came to Willamette with a limited sense of what the world had to offer. I left with an appreciation for the diversity of cultural and social experiences that shaped my life.”

Uncomfortable with such compliments, Duvall gruffly says, “I’m a teacher of great books. I put in front of students the texts of Europe’s great thinkers from the last four centuries. They pose ideas and challenges that push students to think.”

Many of his students, though, vividly recall Duvall’s part in helping them explore those ideas and become critical thinkers. In his classroom, learning is a dynamic activity that requires energy and commitment on the part of both teacher and student. A master of the Socratic method of teaching by questioning, Duvall pushes for in-depth reflection and answers. “Why?” he prods. “What do you mean? But what if?”

“It’s not information delivery,” Duvall says. “It’s about reading, thinking and talking to students. I tend to think of myself as a choreographer; I want the students to dance with me.”

A love of learning

Duvall readily acknowledges that he learns from his students. As they venture on this mutual journey, great teachers make their students feel included and respected. Modeling the best aspects of a liberal arts education, they listen to students’ points of view and remain open to new ideas.

That’s one reason Duvall has never felt stale after decades of teaching. “Students see different things in the readings,” he says. “In one recent discussion in the ‘European Intellectual History of the 19th Century’ class, there were a couple of comments that I’d never thought of before — and I’ve been teaching the text for a long time.”

Memorable teachers revel in the joy of such new discoveries. A former student described chemistry professor Arthur Payton, 1994 Oregon Professor of the Year, in this way: “His formidable command of the subject material is only one component of his teaching magic. Clearly, he has never forgotten what it is like to be a student (in fact, he approaches his subject with a student’s wonder). He gives the strong sense that science is about unraveling the mysteries of the world.”

Politics professor Richard Ellis, the 2008 Oregon Professor of the Year, incorporated research by his students into some of the books he published — and publicly thanked those 33 undergrads in the books’ acknowledgement pages.

One of those research assistants said, “He asked for my opinions and treated them with seriousness and respect. Few things inspire a student more than being treated as a partner by someone they deeply admire.”

High expectations

Although countless students enjoyed Duvall’s challenging approach to learning, others bemoaned the fact that his tough courses lowered their GPA. One undergrad, only half in jest, said: “You had to have, actually, you know, READ the material to actively participate in class discussions.”

Many of Willamette’s undergraduate classes are on par with graduate-level courses at other institutions. While they set exacting standards, professors provide their students with the tools and knowledge to reach their full potential.

Professor emerita Frances Chapple, who became Willamette’s first Oregon Professor of the Year in 1990, taught physical chemistry — a subject rife with difficult and abstract concepts. The entire class often met late at night to work through the problem sets, and their professor would frequently join them to share her expertise. Chapple’s intense love for her subject, along with her contagious energy and enthusiasm, inspired her undergrads to excel.

“The challenge, rigor and level of commitment expected of us was exceeded only by her commitment to us,” said one student. “She encourages us to respond and perform simply by virtue of her enormous dedication to us.”

Mentors and role models

As experts and specialists in their field, Willamette professors often do more than teach. They conduct research, create works of art, write numerous books and articles, and forge professional networks that they willingly share with students to help with internships and potential careers.

Physics professor Daniel Montague, who received the Oregon Professor of the Year Award in 1995, took his undergrad students every year to conduct research and experiments at the Intense Pulsed Neutron Source at the Argonne National Laboratory near Chicago.

Willamette sophomores performed as well as graduate students, recalls a professor from another university, who adds, “It was because the students always knew where they were headed, how certain — but not all — difficulties were to be overcome, where they could go for help, and how the work was the responsibility of all. Then there was the example that Montague himself set: how to comport oneself, work hard, and enjoy that hard work and the fruits it bore.”

Years after graduating from Willamette, many students stay in touch with the mentors who provided critical advice and support.

Students of politics professor Suresht Bald, the 2003 Oregon Professor of the Year, recall her door always being open for undergrads. “The mentoring I received from her was unequaled during my later graduate studies, and I sometimes called upon her for assistance and guidance,” wrote one. “She recognizes that a true teacher’s job does not end on graduation day.”

Chemistry professor Karen Holman, the 2010 Oregon Professor of the Year, earned her students’ admiration and respect as a strong, positive role model of a successful woman in a scientific career. Wrote one student, “Her success in her career, family life and personal interests provide an example everyone should have in their formative years.”

Duvall inspired a number of students to follow his path into academe. Associate professor of history Wendy Petersen Boring ’89 credits him with helping her decide to pursue graduate studies in history rather than law school. She says, “He gave me a vision for a life formed by a passion for thinking and teaching.”

Committed and caring

For many Willamette professors, providing that kind of life-changing education doesn’t just happen in the classroom, lab or music studio. Professors meet students for coffee and a chat at The Bistro. They invite them to dinner at their houses, where intense discussions on philosophy or politics carry on far into the night. They hold impromptu study sessions during evenings or weekends.

Generous with their time, as well as their knowledge, they provide a reassuring presence when students are ill or stricken with crises of confidence. Boring describes Duvall’s enduring compassion for students who were sick, angry, on academic probation, lost or directionless: “They all tell of him taking the time to find them after class in the library or The Bistro, in order to encourage them, to listen, to help, to walk them to find help, to introduce them to other faculty, to make them feel worthwhile and welcome.”

Similarly, Holman took a group of first-years on a walking tour of town, pointing out her favorite restaurants and introducing them to her friends in the record store. It was, according to one student, an example of Holman’s “eagerness to invest herself personally in us and what we were trying to learn, not only in her class but in the college experience at-large.”

Such commitment to students helped affirm Duvall’s decision to stay at Willamette for almost five decades. “I’ve never really been tempted to go anywhere else,” he says. “My goal was to be in a classroom, with only about 15 students. That’s a privilege.”

As he looks back on a career filled with accomplishments and friendships, Duvall says he’s most grateful for “the wonderful stream of students who’ve come through my life and classroom.”

For Bill Duvall, like Willamette’s other great professors, it’s always — first and foremost — been about the students.

This article originally appeared in the summer 2016 edition of Willamette magazine. What did you think of this article? Send your comments to magazine@willamette.edu.

Impressive numbers

Since he arrived on campus in 1971, Bill Duvall has taught an estimated 4,200 students, representing about 20 percent of all Willamette undergraduate alumni.

Although Duvall retired at the end of this past semester, he’ll continue to have a positive effect on students through a scholarship being set up in his name. The Professor William E. “Bill” Duvall Humanities Scholarship will make awards to rising juniors and seniors majoring in one of the College of Liberal Arts’ departments of the humanities (history, English, religious studies, philosophy and art history) who have demonstrated high academic achievement and intellectual curiosity.

To contribute to the scholarship, go to willamette.edu/support/how or call Mike Bennett ’70 at 503-370-6761.

Impressive professors

Since 1989, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and the Council for the Advancement and Support of Higher Education have presented the Oregon Professor of the Year Award to outstanding undergraduate instructors who excel in teaching and positively influence the lives and careers of students.

Willamette has earned more of these honors than any other West Coast institution.

1990 Frances Chapple, chemistry

1991 Mary Ann Youngren, psychology

1993 Roger Hull, art

1994 Arthur Payton, chemistry

1995 Daniel Montague, physics

1998 Bill Duvall, history

2003 Suresht Bald, politics

2005 Jerry Gray, economics

2008 Richard Ellis, politics

2010 Karen McFarlane Holman, chemistry

2013 Sammy Basu, politics