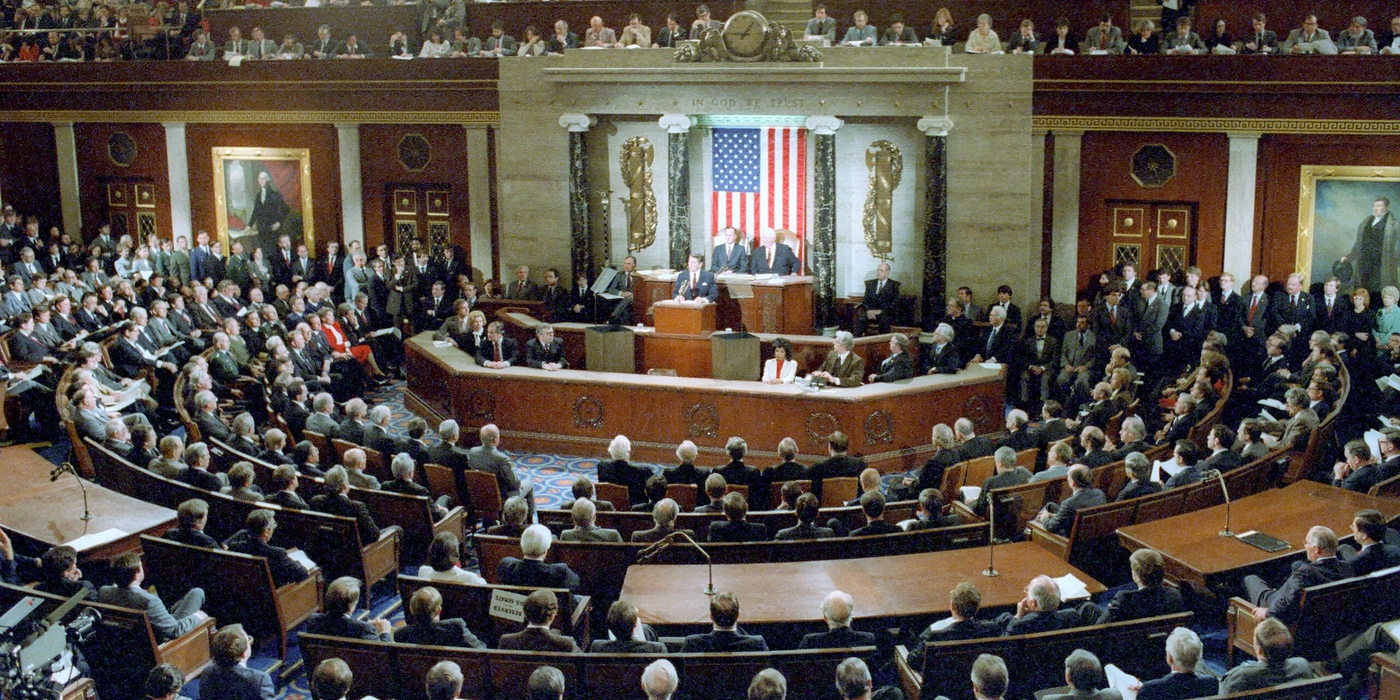

On March 7, President Joseph Biden will walk down the aisle of the House of Representatives Chamber to deliver the State of the Union address, a speech that gives the president of the United States the opportunity to assess national challenges, outline policy priorities, and frame important issues for the nation.

On March 7, President Joseph Biden will walk down the aisle of the House of Representatives Chamber to deliver the State of the Union address, a speech that gives the president of the United States the opportunity to assess national challenges, outline policy priorities, and frame important issues for the nation.

We asked Richard Ellis, Mark O. Hatfield Professor of Politics, Policy, Law and Ethics, for his insight on the 2024 State of the Union address and the evolution of the American presidency. Over his 34-year career at Willamette, Ellis has published extensively on presidential history and American political culture. He teaches courses on the presidency, American exceptionalism, and the initiative and referendum process.

Q: Does the State of the Union address matter in 2024? Why or why not?

If by “matter” you mean changing people’s support for the president and his agenda, then the State of the Union has rarely mattered much. There is some evidence that it can alter what people think is the nation’s most important problem, but that effect is generally short-lived. And the State of the Union’s impact is even more minimal than it used to be because fewer people tune in to the State of the Union than used to be the case and those who do tune in are increasingly the president’s co-partisans. So don’t expect the 2024 State of the Union address to meaningfully affect Biden’s popularity or public support for his agenda.

Q: What challenges do presidents have in communicating their vision to the public in today’s media ecosystem?

The biggest challenge presidents face in today’s fragmented and polarized media environment is to reach and then persuade those who don’t already agree with them. When the three major networks — ABC, CBS, and NBC — ruled the airwaves in the latter half of the twentieth century, presidents who were consistent in their messaging had some hope of reaching a broad spectrum of the public and framing the agenda to their advantage. And while social media gives American presidents new ways to communicate with the public without their words being filtered by the national media, platforms such as Facebook and Twitter/X ultimately exacerbate the problem that presidents are increasingly speaking only to those who already agree with them.

Q: You’ve examined the history of the American presidency. What are some of the ways that the institution has changed since the turn of the 21st century?

In the twentieth century, presidents were often able to govern, even in the face of divided government, by creating issue-specific coalitions that included centrist factions from the other party. The increasing nationalization and polarization of parties incentivizes “strategic disagreement” whereby the opposition opposes a presidential proposal, no matter the content, to avoid giving the president a “win.” The increased use of the filibuster in the U.S. Senate and the Speaker’s refusal to bring issues to a vote in the House means that even when there is a majority favoring a policy in the White House, the Senate, and the House, that policy is unlikely to be enacted, which results in lower presidential approval ratings and lower trust in government.

Presidents have responded by relying more on unilateral directives (i.e. executive orders) to try to affect policy change, but the more ambitious the orders the more likely they are to be overturned in the (increasingly partisan) courts or by the next administration.