You may have experienced Ross Stout’s best work at Willamette University without even realizing it.

For 35 years, Stout BA’85, MBA’93 was the university’s safety director, quietly preventing disruption or disaster from threatening the community.

As Willamette’s first line of defense, his work occurred mostly behind the scenes — from creating general safety policies to overseeing building security — and affected every single person on campus.

After spending nearly his entire professional and academic career here, he has retired. His last day was Jan. 7. A party will be held for him Friday.

On call and ready

Known for his calm and reassuring presence, Stout and his six-person team responded to calls large and small.

They ushered unwelcome visitors off campus, administered first aid and were involved with the response to a devastating 1996 flood, which hit several buildings and closed Goudy Commons for weeks. But their primary duty was to be on call 24 hours a day, ready for anything to happen.

“When the phone rings, you’re always wondering if it’s going to be something that’s too big or too complicated,” Stout said. “That low-level tension is always there.”

Some of the biggest moments of his career were also the most troubling, at least initially. More than two decades ago, when former U.S. Sen. Mark Hatfield BS ’43, R-OR, was visiting Willamette, a campus safety officer discovered a device in the Hatfield Fountain.

Police called the bomb squad and evacuated part of campus. No explosives were found, but the device contained red dye.

Stout believes the device was a form of political protest. Hatfield’s visit happened to be at a time when tensions were still high from the spotted owl controversy, pitting environmentalists against the logging industry over protecting the owl’s preferred habitat. Hatfield supported saving the owl, which halted timber harvest throughout the state.

“The red dye was thought to be a symbol of blood related to the spotted owl, but it was never confirmed,” Stout said.

In the mid-2000s, another questionable object was discovered — a small plastic box sitting in a Doney Hall window well with a note that read, “This is not a bomb. Please do not disturb.” Again, police investigated, this time flooding campus with the bomb squad.

As it turns out, the threat was empty. “It was just a geocache,” Stout laughed.

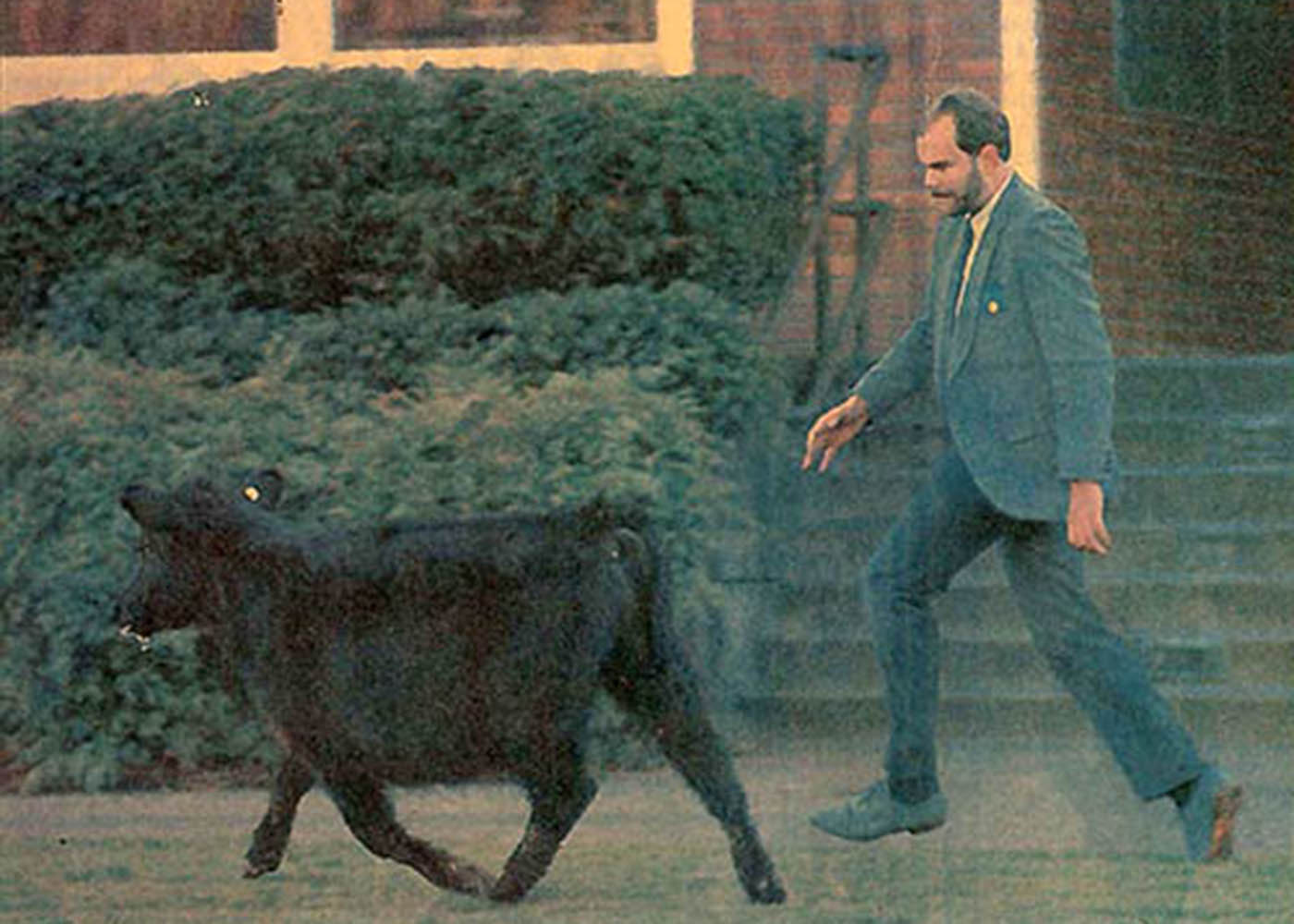

Then there was the cow. In 1988, at the corner of Center and Capitol streets, one of three steers in the back of a stopped truck managed to flip open a canopy door, wander the streets and head straight for Willamette. Stout was front page news. The Statesman Journal headline: “Runaway steak makes break, has posse in its wake.”

Students tried corralling the steer and were joined by state police and campus safety. After trailing it for an hour or so around campus and downtown, an animal control officer shot it with a tranquilizer dart. Undaunted, the steer ran toward a Farm Credit Services building — of course — where an officer finally captured it. “That was my fifteen minutes of fame,“ he said.

Care for community and involvement

Stout began working for Willamette in 1987, after he earned his undergraduate degree in psychology. An earlier career at the Marion County Sheriff’s Office made him realize he needed a job “where innovation and motivation to excel was rewarded, and I found that at Willamette,” he said.

“I had the opportunity to experiment with fun ideas that benefited the community, and I spent my whole career doing that,” he said.

At Willamette, he is best known for co-founding the student-run medical provider, Willamette University Emergency Medical Services, in 1997. For years he also cared for Thetford Lodge, the university’s beloved community retreat near the Santiam River that was destroyed in 2020 by a wildfire. As an auction prize for the Willamette Heritage Center, for which he was a board member and president, he organized a behind the scenes tour of the university, leading guests up the Waller cupola and introducing them to a cadaver in Olin Science Center. He sat on the board for a LGBTQ high school student group called Rainbow Youth, the Salem nonprofit Shangri-La, and supported a nationally recognized threat assessment agency, which he will continue to work for in retirement.

Stout said the greatest satisfaction of his career was assisting the Willamette community.

“I consider it a privilege to have been able to work with all of the people I have, knowing that in some small way I have created an environment that allowed them to safely do what they needed to,” he said.