Nearly 80 years ago, at a small country fair in rural East Texas, a fortune teller asked a young Arvie Smith ’86 what he wanted to be when he grew up.

He paused. He only knew the professions of his grandparents, who were both educators. He had no idea what he wanted to do, so he said the first thing that came to mind.

“I told her, ‘I want to be a doctor,’” he said. “She said, ‘You can be anything you want.’”

At a time of deep racial divisions and chilling violence, near a town known for lynchings long after Reconstruction and later for the brutal death of James Byrd, it was an extraordinary thing to say to an African American child. But he took it to heart.

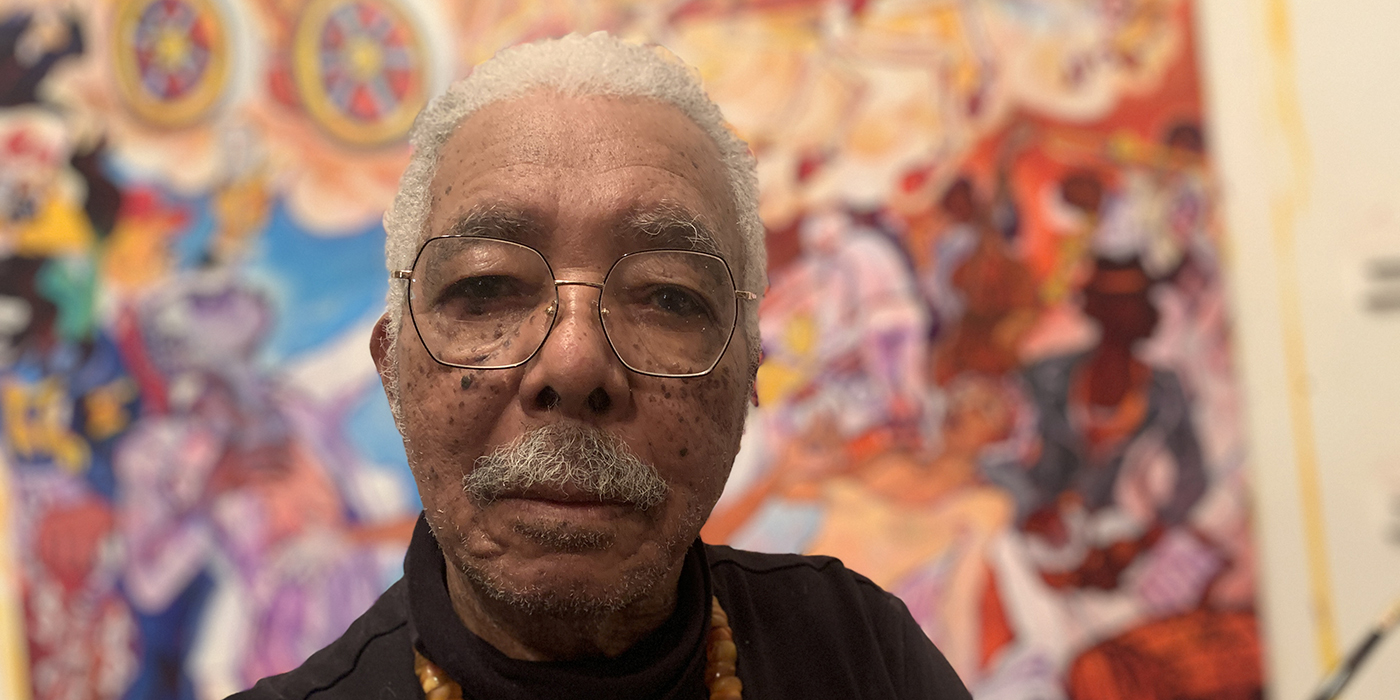

Today Smith’s paintings can be found in many public spaces across Portland, the Nelson Mandela Estate in South Africa and this spring, in Italy. After the current exhibit of his work, “Arvie Smith: Scarecrow,” ends at Hallie Ford Museum of Art on March 26, he will fly to the country to join seven other African American artists selected for an affiliate exhibition at the 2022 Venice Art Biennale, one of the oldest and most prestigious international exhibitions in the world.

“It’s something I never thought I would be a part of,” he said.

Smith’s inclusion represents a larger breakthrough — for the Baltimore-based Galerie Myrtis that represents him, it’s the first time a Black and female-owned gallery was invited to participate in the Biennale exhibition by the European Cultural Center in Italy.

History of persistence

Newcomers to the HFMA exhibit will discover quintessential examples of Smith’s style over the past two decades.

Wildly colorful, arresting and often disturbing, the collective horror of his experience and others is carefully choreographed through a combination of degrading advertising, references to pop culture and current or historical events, resulting in works that mesmerize as much as they enrage.

In “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot,” Smith’s response to the 2014 shooting of a Black youth by a police officer in Ferguson, Aunt Jemima stands front and center, holding up a stack of pancakes in each hand underneath the glare of a TV camera, while a child clings to her back and police barricade tape lines a fence behind her. To her left, a Klansman ushers a young Black woman away underneath Confederate and American flags; to her right, a fire burns near a chalk outline of a body.

“I take some of what’s going on in the world today as I see it, and I deal with it using symbols as a way to talk about it,” he said. “Some of those symbols, like Aunt Jemima, have become icons that influence the way we see our world — not only the way white people see it, but the way Black people see it, too. It’s not the way Black people want to be seen, but we believe it because we have to see ourselves the way white people see us in order to survive.”

Smith has said his voice is art, and he’s been expressing it since he was a child in Jasper, Texas. He first learned how to draw by meticulously copying a book of Michelangelo’s paintings, then he copper-tooled a horse that earned accolades from his great-grandmother, who was born into slavery. As he grew up, the threat of danger was always nearby.

“In the country, there are consequences,” he said. “Right down the road, there were people willing to kill young Black boys. That was the reality.”

The fortune teller’s encouragement — as well as his own moxy — drove him to produce art after he moved to Los Angeles with his family, fell into gangs during high school and was refused admission to an art institute by a receptionist who said, “We don’t need your kind here.” He kept painting, even while working odd jobs in California, Idaho, British Columbia, and when he reached Portland in the mid-’70s, when he started working at Oregon Health and Science University as a counselor at a closed psychiatric unit.

Some years later, at the urging of his soon-to-be wife Julie Kern Smith, he enrolled at Pacific Northwest College of Art at age 42. There he met painter Robert Colescott, who gained prominence for revising famous works by adding blackface to the central characters and becoming the first Black artist to represent the U.S. at the Biennale. Colescott demonstrated to Smith the power of a no-holds-barred approach to racial taboos and stereotypes, and how to challenge them through satire.

Then, after studying painting and printmaking in Florence for a year, Smith graduated from PNCA with his BFA. A fellowship secured his place at the Hoffberger School of Painting at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, where he painted one of his most powerful works — “Strange Fruit,” a nearly 8-foot-tall canvas on which several Klansmen lynch a naked black man — and studied under abstract expressionist Grace Hartigan. A strong supporter of Smith’s art, Hartigan helped his paintings reach galleries in Maryland, Philadelphia and New York City in the ‘90s, broadening his connections and exposure. A journalist Smith met delivered his 1993 painting of a boxer in shorts, “Everlast,” to Nelson Mandela in South Africa for his birthday.

Homecoming

In 1995, it was time for the Smiths to go home.

The late Sally Lawrence, former PNCA president and arts leader, attended a show of Smith’s in New York and offered him a job if he returned. Hartigan discouraged him — “She told me, if you go back to Portland, you’ll be a big fish in a small pond, and nothing is happening (in the art scene) there,” he said — but he and his wife, who wanted to return to the Pacific Northwest, were ready.

Smith taught at PNCA for over 20 years, exhibiting his work in multiple galleries, colleges and museums throughout Portland and Baltimore. He traveled to West Africa over a 12-year-period, in part to inform his art but also to experience his own ancestry.

“Our history has always been told by other people. Since the time of slavery, we weren’t able to read or write,” he said. “We’ve had 500 years of derogatory images and omissions, and a slanted view of the history of African Americans in America. I’ve had a hard time with the idea of people of color being a minority – I’ve been to Africa a number of times, and we’re the most populous people on the planet. Africans were the first people. So, we’re seen through the lens of slavery, but that’s only a short period of our existence.”

In Smith’s last year teaching at PNCA, gallerist Myrtis Bedolla offered to represent him. He has gone on to receive the Oregon Governor’s Arts Award for Lifetime Achievement, land a solo exhibition at the Portland Art Museum (which acquired “Strange Fruit” in 2016), and continues to use his art to engage and as a form of protest. Instead of hitting the streets after George Floyd was murdered in 2020, he had 1,000 posters printed of his Martin Luther King Boulevard mural, “Still We Rise,” and handed them out to community members.

For the affiliate exhibition at the Biennale, Myrtis artists followed the theme “The Afro-Futurist Manifesto: Blackness Reimagined.”

Smith focused on Greek mythology to make the point that Afrofuturism is similarly make-believe, and he wants to continue pursuing the theme when he returns. He’s fascinated with Greek mythology and says the carefully constructed, derogatory myths and images describing Black people are no different — both are intended to shape minds and behavior.

“They are made up stories, and I’m having fun playing with these ideas,” he said. “I’m turning these images that have been assigned to people of African descent, and I’m flipping them on their heads.”

As part of his involvement, he will work with incarcerated African Italian youth, similar to a mural project he completed in 2010 with teenagers at Multnomah County’s Donald E. Long Juvenile Detention Center.

With more than half a million visitors anticipated to attend the Biennale, the Smiths view the event as a door that will open Arvie’s work to the exposure and attention it deserves. They’ve got a lot of growth ahead, said his wife.

In March, the Monique Meloche Gallery in Chicago began representing Smith and will feature his work in a solo exhibition next fall. His paintings will also appear at Expo Chicago 2022 next month.

Smith, 83, paints every day. He fulfilled his dream of becoming an artist. “I told the fortune teller I wanted to be a doctor, and 900 years later, I was awarded an honorary Ph.D. (from PNCA) in 2018,” he said. “So she was right.”